Software development is a collaborative job. As a software engineer, you need to share your work with others. But sharing code and collaborating can get complicated. It’s difficult to keep track of various changes that happen during the life-cycle of a software. So development teams rely on version control tools to help with the software collaboration process. Git is one of the most prominent version control tools in the software industry.

Tip: In this tutorial, you will learn how to use the fundamentals of Git. Each section ends with a few questions. You can read the questions before you start reading the section. This will help you understand and pay attention to the important points.

Have fun learning Git!

Git: A Brief Overview

Git is a distributed version control system. It keeps track of any changes you make to your files and folders. It makes it easier to save your work-in-progress. If there is a problem, you can easily check an earlier version of the file or folder. If necessary, you can even revert your whole codebase to an older version.

The development of Git started in 2005. The Linux kernel group used to maintain their code in BitKeeper, a proprietary distributed version control system. However, BitKeeper withdrew its free use of the product. So Linus Torvalds, the creator and principal developer of Linux, designed a new open-source distributed version control system that would meet the requirements of the Linux development community. And Git was born.

As a distributed version control system, Git doesn’t require a centralized authority to keep track of the code. Older centralized version controls like CVS, SVN or Perforce require central servers to maintain the history of changes. Git can keep track of all the changes locally and work peer-to-peer. So it’s more versatile than centralized systems.

Questions:

- Why should you use Git?

- What is the benefit of distributed version control?

Installing Git

For Linux systems installing Git is easy. If you are using a Debian-based distribution like Ubuntu, you can use apt install:

For Fedora, RHEL or CentOS, you can use:

You can check if Git has been installed, using the following command:

It should show you the version of the Git you installed, for example:

Once you have installed Git, it’s time to set up your username and email:

You can check if the configurations have been set properly using the following command:

user.name=yourusername

user.email=yourusername@example.com

Tip: It’s important to set the user.name and user.email because these configurations are used to track your changes.

Questions

- What is the command for installing Git on your Linux system?

- Why should you set up user.name and user.email configuration? How do you set them up?

Understanding Git Conceptually

In order to use Git, first you need to understand these four concepts:

- Working Directory

- Staging Area

- Repository

- Remote Repository

The working directory, the staging area, and the repository are local to your machine. The remote repository can be any other computer or server. Let’s think of these concepts as four boxes that can hold standard A1 papers.

Suppose you are writing a document by hand on an A1 paper at your desk. You keep this document in the working directory box. At a certain stage of your work, you decide that you are ready to keep a copy of the work you have already done. So you make a photocopy of your current paper and put it in the staging box.

The staging box is a temporary area. If you decide to discard the photocopy in the staging box and update it with a new copy of the working directory document there will be no permanent record of that staged document.

Suppose you are pretty sure that you want to keep the permanent record of the document you have in the staging box. Then you make a photocopy of the staging box document and move it to the repository box.

When you move it to the repository box, two things happen:

- A snapshot of the document is saved permanently.

- A log file entry is made to go with the snapshot.

The log entry will help you find that particular snapshot of your document if you need it in the future.

Now, in the local repository box, you have a snapshot of your work and a log entry. But it’s only available to you. So you make a copy of your local repository document along with the log file and put it in a box in the company supply room. Now anyone in your company can come and make a copy of your document and take it to their desk. The box in the supply room would be the remote repository.

The remote repository is kind of like sharing your document using Google Docs or Dropbox.

Questions:

- Can you define working directory, staging, repository and remote repository?

- Can you draw how documents move from one stage to another?

Your First Git Repository

Once you have Git installed, you can start creating your own Git repositories. In this section, you are going to initialize your Git repository.

Suppose you’re working on a web development project. Let’s create a folder called project_helloworld and change into the directory:

$ cd project_helloworld

You can tell Git to monitor this directory with the following command:

You should see an output like this:

project_helloworld/.git

Now any files and folders inside project_helloworld will be tracked by Git.

Questions:

- How do you initialize a directory to be tracked by Git?

Basic Git Commands: status, log, add, and commit

The status command shows the current condition of your working directory and the log command shows the history. Let’s try the status command:

On branch master

Initial commit

nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)

The output of the git status command is saying that you’re on the master branch. This is the default branch that Git initializes. (You can create your own branches. More about branches later). Also, the output is saying there is nothing to commit.

Let’s try the log command:

fatal: your current branch ‘master’ does not have any commits yet

So, it’s time to create some code. Let’s create a file called index.html:

You can use the text editor to create the file. Once you have saved the file, check the status again:

On branch master

Initial commit

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>…" to include in what will be committed)

index.html

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

Git is telling you that you have a file called index.html in your working directory that is untracked.

Let’s make sure index.html is tracked. You will need to use the add command:

Alternatively, you could use the “.” Option to add everything in the directory:

Now let’s check the status again:

On branch master

Initial commit

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm –cached <file>…" to unstage)

new file: index.html

The green indicates that the index.html file is being tracked by Git.

Tip: As mentioned in the instructions above, if you use the command:

Your index.html will go back to untracked status. You’ll have to add it again to bring it back to staging.]

Let’s check the log again:

fatal: your current branch ‘master’ does not have any commits yet

So even though Git is tracking index.html, there isn’t anything in the Git repository about the file yet. Let’s commit our changes:

The output should look something like this:

[master (root-commit) f136d22] Committing index.html

1 file changed, 6 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 index.html

The text inside the quotes after the “-m” is a comment that will go into the log file. You can use git commit without “-m”, but then Git will open up a text editor asking you to write the comments. It’s easier to just put the comments directly on the command line.

Now let’s check our log file:

commit f136d22040ba81686c9522f4ff94961a68751af7

Author: Zak H <zakh@example.com>

Date: Mon Jun 4 16:53:42 2018 -0700

Committing index.html

You can see it is showing a commit. You have successfully committed your changes to your local repository. If you want to see the same log in a concise way, you can use the following command:

f136d22 Committing index.html

Moving forward, we will use this form of the log command because it makes it easier to understand what is going on.

Let’s start editing the index.html. Open the index.html file in an editor and change the “Hello world” line to “Hello world! It’s me!” and save it. If you check the status again, you’ll see Git has noticed that you’re editing the file:

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>…" to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout — <file>…" to discard changes in working directory)

modified: index.html

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

The change is still in your working directory. You need to push it to the staging area. Use the add command you used before:

Check the status again:

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>…" to unstage)

modified: index.html

Now your changes are in the staging area. You can commit it to the repository for permanent safekeeping:

[master 0586662] Modified index.html to a happier message

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(–)

You can check the log for your permanent changes:

0586662 Modified index.html to a happier message

f136d22 Committing index.html

In this section, you have learned to use status, log, add and commit commands to keep track of your documents in Git.

Questions:

- What does git status do?

- What does git log do?

- What does git add do?

- What does git commit do?

Going Back to Older Files Using Checkout

When you commit a file in Git, it creates a unique hash for each commit. You can use these as identifiers to return to an older version.

Let’s suppose you want to go back to your earlier version of index.html. First, let’s look at the index.html in the current condition:

You can see you have the newer version (“Hello world! It’s me!”). Let’s check the log:

0586662 Modified index.html to a happier message

f136d22 Committing index.html

The hash for the previous version was f136d22 (“Hello world”). You can use the checkout command to get to that version:

Note: checking out ‘f136d22’.

You are in ‘detached HEAD’ state. You can look around, make experimental changes

and commit them, and you can discard any commits you make in this state

without impacting any branches by performing another checkout.

If you want to create a new branch to retain commits you create, you may

do so (now or later) by using -b with the checkout command again. Example:

git checkout -b <new-branch-name>

HEAD is now at f136d22… Committing index.html

If you look at the content of index.html, you’ll see:

It only has “Hello world”. So your index.html has changed to the older version. If you check the status:

HEAD detached at f136d22

nothing to commit, working directory clean

Git is basically telling you that the HEAD is not at the most recent commit. You can go back to the most recent commit by checking out the master branch using the following command:

Previous HEAD position was f136d22… Committing index.html

Switched to branch ‘master’

Now if you check status:

On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory clean

The red warning is gone. Also, if you check your index.html, you should be back to the latest version:

The checkout command gets you to various states. We will learn more about checkout in the next section.

Questions:

- How do you use git checkout command to go to an older version of a file?

- How do you use git checkout to come back to the latest version of the file?

Checkout, Branching, and Merging

Branching is one of Git’s best features. It helps you separate your work and experiment more. In other version control systems, branching was time-consuming and difficult. Git made branching and merging easier.

As you noticed in status command, when you create a new Git repository, you are in the master branch.

On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory clean

Suppose you are making a website for your friend David. You want to reuse the code of your own website. Branching is a great solution. Let’s call the branch david_website.

You can issue the following command:

You can use the following command to see all the branches:

david_website

* master

The star(*) beside master means you are still in the master branch. You can check out the david_website branch with the following command:

Switched to branch ‘david_website’

Now if you again check the branch list, you see:

* david_website

master

So you’re on the david_website branch.

Let’s change the index.html from “Hello world! It’s me!” to “Hello world! It’s David!” and then stage and commit it:

$ git commit -m "Changed website for David"

If you check the logs, you should see:

345c0f4 Changed website for David

0586662 Modified index.html to a happier message

f136d22 Committing index.html

And your index file should look like this:

Now let’s check out the master branch again:

Switched to branch ‘master’

If you check the status and log:

On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory clean

$ git log –oneline

0586662 Modified index.html to a happier message

f136d22 Committing index.html

Notice you don’t have your third commit in the master. Because that commit is only maintained in the david_website branch.

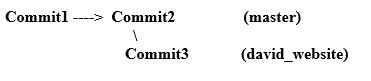

This is what happened

Suppose at this stage you decide, you don’t want to continue your website. You’ll just be the developer for David. So you want to merge the changes in the david_website branch to the master. From the master branch, you just have to issue the following commands (the status command is used to check if you’re in the right place):

On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory clean

$ git merge david_website

Updating 0586662..345c0f4

Fast-forward

index.html | 2 +-

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(–)

Tip: You are pulling changes from david_website to master. You have to be on the master to achieve this.

Now if you check the log on the master, you see the third commit is there:

345c0f4 Changed website for David

0586662 Modified index.html to a happier message

f136d22 Committing index.html

You have successfully merged the david_website branch into master. And your index.html for master branch looks identical to david_website branch:

You can keep the david_website branch:

david_website

* master

Or you can delete it:

Deleted branch david_website (was 345c0f4).

After deletion, you shouldn’t see the david_website branch anymore:

* master

Tip: During a merge, if Git can’t merge automatically it will give you merge conflict errors. In that case, you have to manually solve the merge problems.

Questions:

- Why do you need branching?

- How do you branch and merge files and folders?

Remote Repository

Until now, all your work has been local. You have been committing your changes to a local repository. But it’s time to share your work with the world.

Git remote repository is basically another copy of your local repository that can be accessed by others. You can set up a server and make it the remote repository. But most people use GitHub or Bitbucket for this purpose. You can create public repositories for free there which can be accessed by anyone.

Let’s create a remote repository on GitHub.

First, you need to create a GitHub account[]. Once you have the account, create a new repository using the “New repository” button. Use “project_website” as the repository name (you can choose something else if you want).

You should see a Code tab with instructions like these:

…or create a new repository on the command line

git init

git add README.md

git commit -m "first commit"

git remote add origin git@github.com:yourusername/project_website.git

git push -u origin master

Copy the following “git remote add origin” command and run it in your working directory:

Note: In your case, yourusername should be what you used to create your GitHub account.

In the above command, you instructed Git the location of the remote repository. The command is telling Git that the “origin” for your project_helloworld working directory will be “[email protected]:yourusername/project_website.git”.

Now push your code from your master branch to origin (remote repository):

Counting objects: 9, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (6/6), done.

Writing objects: 100% (9/9), 803 bytes | 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 9 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (2/2), done.

To git@github.com:yourusername/project_website.git

* [new branch] master –> master

If you refresh your browser in GitHub, you should see that the index.html file is up there. So your code is public and other developers can check out and modify code on the remote repository.

As a developer, you’ll be working with other people’s code. So it’s worth trying to checkout code from GitHub.

Let’s go to a new directory where you don’t have anything. On the right side of the GitHub repository, you’ll notice the “Clone or download” button. If you click on it, it should give you an SSH address. Run the following command with the SSH address:

The output should look like this:

Cloning into ‘project_website’…

remote: Counting objects: 9, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (4/4), done.

remote: Total 9 (delta 2), reused 9 (delta 2), pack-reused 0

Receiving objects: 100% (9/9), done.

Resolving deltas: 100% (2/2), done.

Checking connectivity… done.

It will create a project_website in your clean folder. If you go inside, you should see the index.html from your project_helloworld.

So you have achieved the following:

- Created and made changes in project_helloworld

- Uploaded the code to GitHub in project_website

- Downloaded the code from GitHub

Let’s another file from the new working directory project_website:

$ git add .

$ git commit -m "Added ReadMe.md"

$ git push origin master

If you refresh the GitHub project_website page, you should see the ReadMe.md file there.

Note: When you download code from GitHub, the working directory automatically knows the origin. You don’t have to define it with the “git remote add origin” command.

Questions:

- Why do you need to use remote repositories?

- How do you set up your current local repository to connect to the remote repository?

- How do you clone remote repositories to your local computer?

Conclusion

You can find more information about all the commands in the Git docs[]. Even though there are Git UI tools available, command-line is the best way to master Git. It will give you a stronger foundation for your development work.