TensorFlow has found immense use in the field of machine learning, precisely because machine learning involves a lot of number-crunching and is used as a generalized problem solving technique. And although we will be interacting with it using Python, it has front-ends for other languages like Go, Node.js and even C#.

Tensorflow is like a black box that hides all the mathematical subtleties inside it and the developer just calls the right functions to solve a problem. But what problem?

Machine Learning (ML)

Suppose you are designing a bot to play a game of chess. Because of the way chess is designed, the way pieces move, and the well-defined objective of the game, it is quite possible to write a program that would play the game extremely well. In fact, it would outsmart the entire human race in chess. It would know exactly what move it needs to make given the state of all pieces on the board.

However, such a program can only play chess. The game’s rules are baked into the logic of the code and all that program does is execute that logic rigorously and more accurately than any human could. It is not a general purpose algorithm that you can use to design any game bot.

With machine learning, the paradigm shifts and the algorithms become more and more general-purpose.

The idea is simple, it starts by defining a classification problem. For example, you want to automate the process of identifying the species of spiders. The species that are known to you are the various classes (not to be confused with taxonomic classes) and the aim of the algorithm is to sort a new unknown image into one of these classes.

Here, the first step for the human would be to determine the features of various individual spiders. We would supply data about the length, width, body mass and color of individual spiders along with the species to which they belong:

| Length | Width | Mass | Color | Texture | Species |

| 5 | 3 | 12 | Brown | smooth | Daddy Long legs |

| 10 | 8 | 28 | Brown-black | hairy | Tarantula |

Having a large collection of such individual spider data will be used to ‘train’ the algorithm and another similar dataset will be used for testing the algorithm to see how well it does against new information it has never encountered before, but which we already know the answer to.

The algorithm will start off in a randomized way. That is to say, every spider regardless of its features would be classified as anyone of the species. If there are 10 different species in our dataset, then this naive algorithm would be given the correct classification approximately 1/10th of the time because of sheer-luck.

But then the machine-learning aspect would start taking over. It would start associating certain features with certain outcome. For example, hairy spiders are likely to be tarantulas, and so are the larger spiders. So whenever, a new spider which is large and hairy shows up, it will be assigned a higher probability of being tarantula. Notice, we are still working with probabilities, this is because we inherently are working with a probabilistic algorithm.

The learning part works by altering the probabilities. Initially, the algorithm starts by randomly assigning a ‘species’ labels to individuals by making random correlations like, being ‘hairy’ and being ‘daddy long legs’. When it makes such a correlation and the training dataset doesn’t seem to agree with it, that assumption is dropped.

Similarly, when a correlation works well through several examples, it gets stronger each time. This method of stumbling towards the truth is remarkably effective, thanks to a lot of the mathematical subtleties that, as a beginner, you wouldn’t want to worry about.

TensorFlow and training your own Flower classifier

TensorFlow takes the idea of machine learning even further. In the above example, you were in charge of determining the features that distinguishes one species of spider from another. We had to measure individual spiders painstakingly and create hundreds of such records.

But we can do better, by providing just raw image data to the algorithm, we can let the algorithm find patterns and understand various things about the image like recognizing the shapes in the image, then understanding what’s the texture of different surfaces are, the color, so on and so forth. This is the beginning notion of computer vision and you can use it for other kind of inputs too, like audio signals and training your algorithm for voice recognition. All of this comes under the umbrella term of ‘Deep Learning’ where machine learning is taken to its logical extreme.

This generalized set of notions can then be specialized when dealing with a lot of images of flowers and categorizing them.

In the example below we will be using a Python2.7 front-end to interface with TensorFlow and we will be using pip (not pip3) to install TensorFlow. The Python 3 support is still a little buggy.

To make your own image classifier, using TensorFlow first let’s install it using pip:

Next, we need to clone the tensorflow-for-poets-2 git repository. This is a really good place to start for two reasons:

- It is simple and easy to use

- It comes pre-trained to a certain degree. For example, the flower classifier is already trained to understand what texture it is looking at and what shapes it is looking at so it is computationally less intensive.

Let’s get the repository:

$cd tensorflow-for-poets-2

This is going to be our working directory, so all the commands should be issued from within it, from now on.

We still need to train the algorithm for the specific problem of recognizing flowers, for that we need training data, so let’s get that:

| tar xz -C tf_files

The directory …./tensorflow-for-poets-2/tf_files contains a ton of these images properly labeled and ready to be used. The images will be for two different purposes:

- Training the ML program

- Testing the ML program

You can check the contents of the folder tf_files and here you will find that we are narrowing down to only 5 categories of flowers, namely daisies, tulips, sunflowers, dandelion, and roses.

Training the model

You can start the training process by first setting up the following constants for resizing all input images into a standard size, and using a light-weight mobilenet architecture:

$ARCHITECTURE="mobilenet_0.50_${IMAGE_SIZE}"

Then invoke the python script by running the command:

–bottleneck_dir=tf_files/bottlenecks

–how_many_training_steps=500

–model_dir=tf_files/models/

–summaries_dir=tf_files/training_summaries/"${ARCHITECTURE}"

–output_graph=tf_files/retrained_graph.pb

–output_labels=tf_files/retrained_labels.txt

–architecture="${ARCHITECTURE}"

–image_dir=tf_files/flower_photos

While there are a lot of options specified here, most of them specify your input data directories and the number of iteration, as well as the output files where the information about the new model would be stored. This shouldn’t take longer than 20 minutes to run on a mediocre laptop.

Once the script finishes both training and testing it will give you an accuracy estimate of the trained model, which in our case was slightly higher than 90%.

Using the trained model

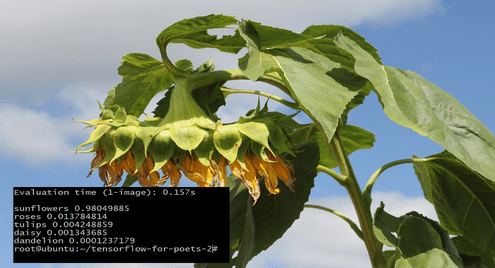

You are now ready to use this model for the image recognition of any new image of a flower. We will be using this image:

The face of the sunflower is barely visible and this is a great challenge for our model:

To get this image from Wikimedia commons use wget:

$mv Sunflower_head_2011_G1.jpg tf_files/unknown.jpg

It is saved as unknown.jpg under the tf_files subdirectory.

Now, for the moment of truth, we shall see what our model has to say about this image.To do that, we invoke the label_image script:

image=tf_files/unknown.jpg

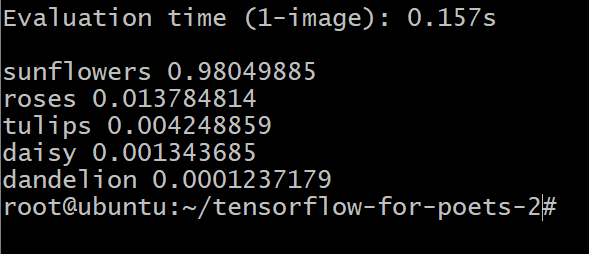

You would get an output similar to this:

The numbers next to the flower type represent the probability that our unknown image belongs to that category. For example, it is 98.04% certain that the image is of a sunflower and it is only 1.37% chance of it being a rose.

Conclusion

Even with a very mediocre computational resources, we are seeing a staggering accuracy at identifying images. This clearly demonstrates the power and flexibility of TensorFlow.

From here on, you can start experimenting with various other kind of inputs or try to start writing your own different application using Python and TensorFlow. If you want to know the internal working of machine learning a little better here is an interactive way for you to do so.