From Source Code To Binary Code

Programming starts with having a clever idea, and writing source code in a programming language of your choice, for example C, and saving the source code in a file. With the help of an adequate compiler, for example GCC, your source code is translated into object code, first. Eventually, the linker translates the object code into a binary file that links the object code with the referenced libraries. This file contains the single instructions as machine code that are understood by the CPU, and are executed as soon the compiled program is run.

The binary file mentioned above follows a specific structure, and one of the most common ones is named ELF that abbreviates Executable and Linkable Format. It is widely used for executable files, relocatable object files, shared libraries, and core dumps.

Twenty years ago – in 1999 – the 86open project has chosen ELF as the standard binary file format for Unix and Unix-like systems on x86 processors. Luckily, the ELF format had been previously documented in both the System V Application Binary Interface, and the Tool Interface Standard [4]. This fact enormously simplified the agreement on standardization between the different vendors and developers of Unix-based operating systems.

The reason behind that decision was the design of ELF – flexibility, extensibility, and cross-platform support for different endian formats and address sizes. ELF’s design is not limited to a specific processor, instruction set, or hardware architecture. For a detailed comparison of executable file formats, have a look here [3].

Since then, the ELF format is in use by several different operating systems. Among others, this includes Linux, Solaris/Illumos, Free-, Net- and OpenBSD, QNX, BeOS/Haiku, and Fuchsia OS [2]. Furthermore, you will find it on mobile devices running Android, Maemo or Meego OS/Sailfish OS as well as on game consoles like the PlayStation Portable, Dreamcast, and Wii.

The specification does not clarify the filename extension for ELF files. In use is a variety of letter combinations, such as .axf, .bin, .elf, .o, .prx, .puff, .ko, .so, and .mod, or none.

The Structure of an ELF File

On a Linux terminal, the command man elf gives you a handy summary about the structure of an ELF file:

Listing 1: The manpage of the ELF structure

ELF(5) Linux Programmer’s Manual ELF(5)

NAME

elf – format of Executable and Linking Format (ELF) files

SYNOPSIS

#include <elf.h>

DESCRIPTION

The header file <elf.h> defines the format of ELF executable binary

files. Amongst these files are normal executable files, relocatable

object files, core files and shared libraries.

An executable file using the ELF file format consists of an ELF header,

followed by a program header table or a section header table, or both.

The ELF header is always at offset zero of the file. The program

header table and the section header table’s offset in the file are

defined in the ELF header. The two tables describe the rest of the

particularities of the file.

…

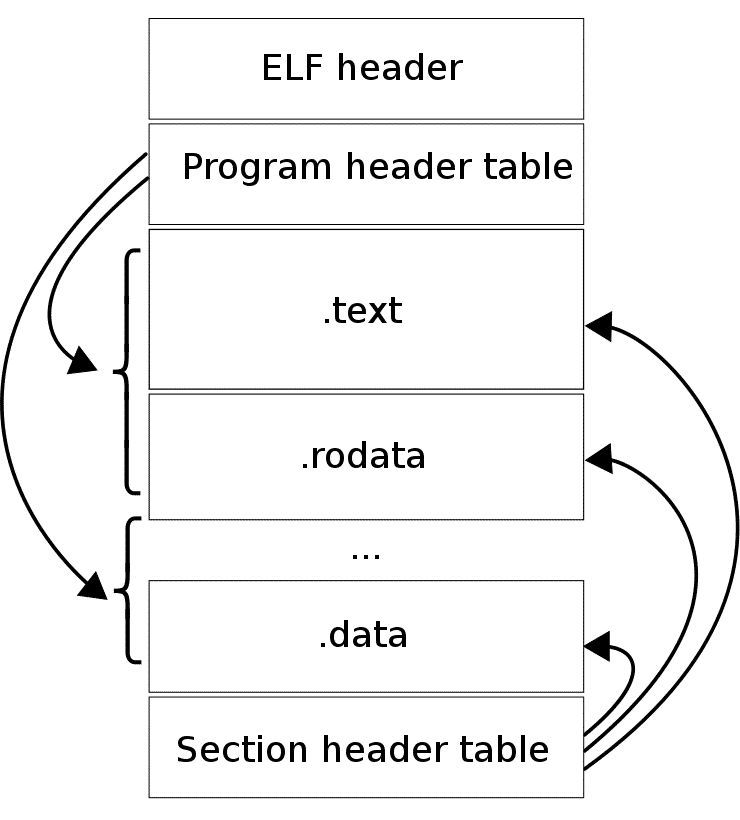

As you can see from the description above, an ELF file consists of two sections – an ELF header, and file data. The file data section can consist of a program header table describing zero or more segments, a section header table describing zero or more sections, that is followed by data referred to by entries from the program header table, and the section header table. Each segment contains information that is necessary for run-time execution of the file, while sections contain important data for linking and relocation. Figure 1 illustrates this schematically.

The ELF Header

The ELF header is 32 bytes long, and identifies the format of the file. It starts with a sequence of four unique bytes that are 0x7F followed by 0x45, 0x4c, and 0x46 which translates into the three letters E, L, and F. Among other values, the header also indicates whether it is an ELF file for 32 or 64-bit format, uses little or big endianness, shows the ELF version as well as for which operating system the file was compiled for in order to interoperate with the right application binary interface (ABI) and cpu instruction set.

The hexdump of the binary file touch looks as follows:

.Listing 2: The hexdump of the binary file

00000000 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.ELF…………|

00000010 02 00 3e 00 01 00 00 00 e3 25 40 00 00 00 00 00 |..>……%@…..|

00000020 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 28 e4 00 00 00 00 00 00 |@…….(…….|

00000030 00 00 00 00 40 00 38 00 09 00 40 00 1b 00 1a 00 |…[email protected]…@…..|

00000040 06 00 00 00 05 00 00 00 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |……..@…….|

Debian GNU/Linux offers the readelf command that is provided in the GNU ‘binutils’ package. Accompanied by the switch -h (short version for “–file-header”) it nicely displays the header of an ELF file. Listing 3 illustrates this for the command touch.

.Listing 3: Displaying the header of an ELF file

ELF Header:

Magic: 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Class: ELF64

Data: 2’s complement, little endian

Version: 1 (current)

OS/ABI: UNIX – System V

ABI Version: 0

Type: EXEC (Executable file)

Machine: Advanced Micro Devices X86-64

Version: 0x1

Entry point address: 0x4025e3

Start of program headers: 64 (bytes into file)

Start of section headers: 58408 (bytes into file)

Flags: 0x0

Size of this header: 64 (bytes)

Size of program headers: 56 (bytes)

Number of program headers: 9

Size of section headers: 64 (bytes)

Number of section headers: 27

Section header string table index: 26

The Program Header

The program header shows the segments used at run-time, and tells the system how to create a process image. The header from Listing 2 shows that the ELF file consists of 9 program headers that have a size of 56 bytes each, and the first header starts at byte 64.

Again, the readelf command helps to extract the information from the ELF file. The switch -l (short for –program-headers or –segments) reveals more details as shown in Listing 4.

.Listing 4: Display information about the program headers

Elf file type is EXEC (Executable file)

Entry point 0x4025e3

There are 9 program headers, starting at offset 64

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr

FileSiz MemSiz Flags Align

PHDR 0x0000000000000040 0x0000000000400040 0x0000000000400040

0x00000000000001f8 0x00000000000001f8 R E 8

INTERP 0x0000000000000238 0x0000000000400238 0x0000000000400238

0x000000000000001c 0x000000000000001c R 1

[Requesting program interpreter: /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2]

LOAD 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000400000 0x0000000000400000

0x000000000000d494 0x000000000000d494 R E 200000

LOAD 0x000000000000de10 0x000000000060de10 0x000000000060de10

0x0000000000000524 0x0000000000000748 RW 200000

DYNAMIC 0x000000000000de28 0x000000000060de28 0x000000000060de28

0x00000000000001d0 0x00000000000001d0 RW 8

NOTE 0x0000000000000254 0x0000000000400254 0x0000000000400254

0x0000000000000044 0x0000000000000044 R 4

GNU_EH_FRAME 0x000000000000bc40 0x000000000040bc40 0x000000000040bc40

0x00000000000003a4 0x00000000000003a4 R 4

GNU_STACK 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 RW 10

GNU_RELRO 0x000000000000de10 0x000000000060de10 0x000000000060de10

0x00000000000001f0 0x00000000000001f0 R 1

Section to Segment mapping:

Segment Sections…

00

01 .interp

02 .interp .note.ABI-tag .note.gnu.build-id .gnu.hash .dynsym .dynstr .gnu.version .gnu.version_r .rela.dyn .rela.plt .init .plt .text .fini .rodata .eh_frame_hdr .eh_frame

03 .init_array .fini_array .jcr .dynamic .got .got.plt .data .bss

04 .dynamic

05 .note.ABI-tag .note.gnu.build-id

06 .eh_frame_hdr

07

08 .init_array .fini_array .jcr .dynamic .got

The Section Header

The third part of the ELF structure is the section header. It is meant to list the single sections of the binary. The switch -S (short for –section-headers or –sections) lists the different headers. As for the touch command, there are 27 section headers, and Listing 5 shows the first four of them plus the last one, only. Each line covers the section size, the section type as well as its address and memory offset.

.Listing 5: Section details revealed by readelf

There are 27 section headers, starting at offset 0xe428:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Address Offset

Size EntSize Flags Link Info Align

[ 0] NULL 0000000000000000 00000000

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0 0 0

[ 1] .interp PROGBITS 0000000000400238 00000238

000000000000001c 0000000000000000 A 0 0 1

[ 2] .note.ABI-tag NOTE 0000000000400254 00000254

0000000000000020 0000000000000000 A 0 0 4

[ 3] .note.gnu.build-i NOTE 0000000000400274 00000274

…

…

[26] .shstrtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 0000e334

00000000000000ef 0000000000000000 0 0 1

Key to Flags:

W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge), S (strings), l (large)

I (info), L (link order), G (group), T (TLS), E (exclude), x (unknown)

O (extra OS processing required) o (OS specific), p (processor specific)

Tools to Analyze an ELF file

As you may have noted from the examples above, GNU/Linux is fleshed out with a number of useful tools that help you to analyze an ELF file. The first candidate we will have a look at is the file utility.

file displays basic information about ELF files, including the instruction set architecture for which the code in a relocatable, executable, or shared object file is intended. In listing 6 it tells you that /bin/touch is a 64-bit executable file following the Linux Standard Base (LSB), dynamically linked, and built for the GNU/Linux kernel version 2.6.32.

.Listing 6: Basic information using file

/bin/touch: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/l,

for GNU/Linux 2.6.32, BuildID[sha1]=ec08d609e9e8e73d4be6134541a472ad0ea34502, stripped

$

The second candidate is readelf. It displays detailed information about an ELF file. The list of switches is comparably long, and covers all the aspects of the ELF format. Using the switch -n (short for –notes) Listing 7 shows the note sections, only, that exist in the file touch – the ABI version tag, and the build ID bitstring.

.Listing 7: Display Selected sections of an ELF file

Displaying notes found at file offset 0x00000254 with length 0x00000020:

Owner Data size Description

GNU 0x00000010 NT_GNU_ABI_TAG (ABI version tag)

OS: Linux, ABI: 2.6.32

Displaying notes found at file offset 0x00000274 with length 0x00000024:

Owner Data size Description

GNU 0x00000014 NT_GNU_BUILD_ID (unique build ID bitstring)

Build ID: ec08d609e9e8e73d4be6134541a472ad0ea34502

Note that under Solaris and FreeBSD, the utility elfdump [7] corresponds with readelf. As of 2019, there has not been a new release or update since 2003.

Number three is the package named elfutils [6] that is purely available for Linux. It provides alternative tools to GNU Binutils, and also allows validating ELF files. Note that all the names of the utilities provided in the package start with eu for ‘elf utils’.

Last but not least we will mention objdump. This tool is similar to readelf but focuses on object files. It provides a similar range of information about ELF files and other object formats.

.Listing 8: File information extracted by objdump

/bin/touch: file format elf64-x86-64

architecture: i386:x86-64, flags 0x00000112:

EXEC_P, HAS_SYMS, D_PAGED

start address 0x00000000004025e3

$

There is also a software package called ‘elfkickers’ [9] which contains tools to read the contents of an ELF file as well as manipulating it. Unfortunately, the number of releases is rather low, and that’s why we just mention it, and do not show further examples.

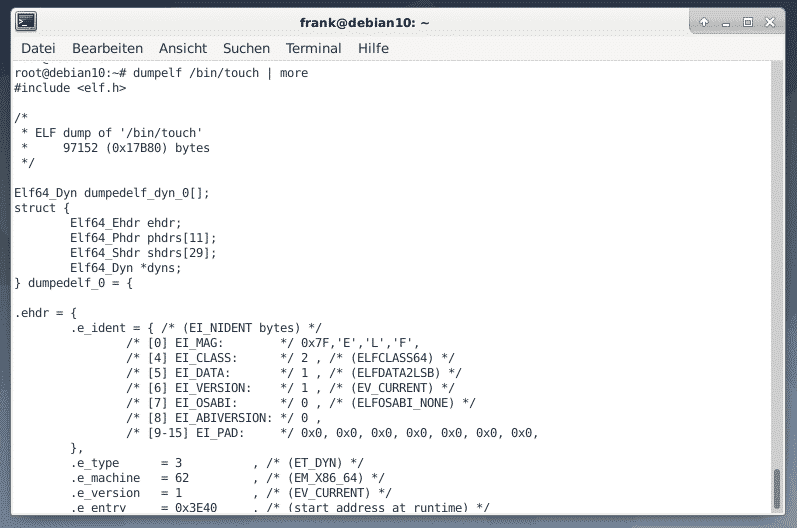

As a developer you may have a look at ‘pax-utils’ [10,11], instead. This set of utilities provides a number of tools that help to validate ELF files. As an example, dumpelf analyzes the ELF file, and returns a C header file containing the details – see Figure 2.

Conclusion

Thanks to a combination of clever design and excellent documentation the ELF format works very well, and is still in use after 20 years. The utilities shown above allow you an insight view into an ELF file, and let you figure out what a program is doing. These are the first steps for analyzing software – happy hacking!

Links and References

- [1] Executable and Linkable Format (ELF), Wikipedia

- [2] Fuchsia OS

- [3] Comparison of executable file formats, Wikipedia

- [4] Linux Foundation, Referenced Specifications

- [5] Ciro Santilli: ELF Hello World Tutorial

- [6] elfutils Debian package

- [7] elfdump

- [8] Michael Boelen: The 101 of ELF files on Linux: Understanding and Analysis

- [9] elfkickers

- [10] Hardened/PaX Utilities

- [11] pax-utils, Debian package

Acknowledgements

The writer would like to thank Axel Beckert for his support regarding the preparation of this article.